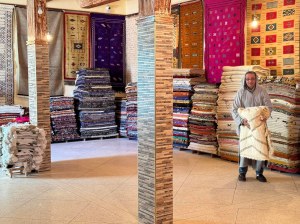

I arrived in Morocco on December 16, 2024 with a loose itinerary and an even looser idea of what the next few months would look like. I had an approximate date circled on my calendar. I would leave in early April, stop in Marrakech to meet friends, then fly to Paris for two weeks with another friend. After that, I’d wander somewhere undetermined for a while, before making my way to Bulgaria by the end of June. Simple, and at least somewhat predictable.

But Morocco had other plans for me.

This country has a way of loosening your grip on timelines. And those of you who know me know this isn’t the first time I’ve lost track of time and stayed far longer in another country than I originally planned. Here, the days stretched out, strangers became family, and volunteers flowed in and out. Each one leaving new friendships in their wake and planting seeds for future reunions in their countries or somewhere else in the world. Slowly, the version of yourself you thought you were begins to shift into someone different with different ideas and plans. And somewhere along the way, time kept passing and I simply… never left.

Now, over a year later, I’m still here. Even before my back injury extended my stay, the path I thought I was following had already begun to reroute itself, subtly, in ways I didn’t realize until much later.

On January 1, 2025, I was living a simple life in Tabounte, Morocco, with an Amazigh/Berber/Nomad family. Even though the new year isn’t a significant date on their calendar, much like Christmas, they still wanted to make it special for me. We kicked off the year with a picnic in a park several miles from our home, a day filled with laughter, games, and more good food than we could possibly finish. We’d hired a van to take us there, but the walk home would be on foot.

The long journey back was more than I bargained for, but the stunning sunset that followed us almost made every step worthwhile. By the time we finally reached home, I was exhausted, yet fulfilled in every way that mattered.

As my time with my family was drawing to a close. My friend, Eric, was on his way to visit me in Morocco, and once his trip ended, I planned to move on to another WorkAway. As is often the case, the universe had other ideas. I couldn’t have known then that the next chapter would take a turn I never saw coming.

But before moving on, there was one final, unforgettable punctuation mark: a two-day journey deep into the Sahara. Fifty miles in, to Erg Chigaga, the highest dunes in the desert, where we found ourselves less than nine miles from the Algerian border. That night, gathered around a fire beneath a full moon, the sky revealed a rare alignment: Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Neptune, and Saturn, all visible at once. Before the moon rose, the Milky Way burned so brightly it felt close enough to touch.

In the early morning hours, as temperatures dipped below freezing, I woke and stepped barefoot into the cold sand. It brought me back to a night in 2016 at Everest Base Camp, another place where the world had gone quiet and vast all at once. Emotion washed over me. In that moment, I felt as though I were the only person on the planet.

The desert was pure magic.

Then on a crisp, sunlit Sunday morning in late January, I boarded a bus bound for Marrakech, a 4½-hour journey that would carry me over the Atlas Mountains and into whatever came next. Eric was heading the other way, toward Casablanca, before returning to the United States. Our paths diverged, as they so often do because travel teaches you how temporary everything is.

The night before, Eric asked me what I found hardest to leave behind. It wasn’t the first time I’d been asked that question, nor the first time I’d faced it. I’ve left cities and countries, friendships and chapters of my life. I know that material things are replaceable. You can buy another sweater, find another apartment, learn another route through unfamiliar streets. What you can’t replace so easily is your heart.

In just five weeks, these people had become my family. Somewhere between shared meals and quiet moments, laughter and routine, I had grown rooted without realizing it. I may be well-versed in the art of leaving, but it’s rarely painless.

And then there is the subtler loss, the version of yourself you leave behind. The person you were in that time and place, shaped by those faces, that way of life, that sense of belonging. You can carry the memories forward, but you will never be exactly that person again.

The plan was simple enough on paper: one night in Marrakech, an afternoon flight to London Stansted, one night there, then back to Marrakech. A quick visa reset, just enough days added so I could remain in Morocco while my friends visited.

Somewhere over the Atlas Mountains, my left ear popped and stubbornly refused to unpop. By the time I landed in London, I was dizzy, unsteady, and knew something wasn’t right, and my ear had taken an oozy turn I won’t describe in detail here. I checked into my hotel, grabbed fast food to eat in bed, and stayed there until it was time to return to the airport the next day.

Back in Marrakech, I went straight from the airport to my hotel and back under the covers. I was supposed to head to a WorkAway about an hour outside of Agadir two days later, but my body had other ideas. Thankfully, the hotel was able to extend my stay and arrange a visit to a clinic, because whatever was going on wasn’t improving. It turned out I had somehow damaged my eardrum and developed a middle ear infection.

The Agadir WorkAway was no longer an option. Instead, I found a last-minute placement in Attaouia that could take me as soon as I was well enough to travel. A few days before I was set to leave, the school there asked if I would be willing to go instead to their sister school in Kelaa.

After a week spent recovering in my little oasis, I boarded a bus on January 28th bound for Kelaa. And that, my friends, is how I ended up in a city that seemed to have a grip on me from the start. My plan to leave Morocco in April was still penciled into my calendar, but it would never quite make it off the page.

I arrived in Kelaa on a Tuesday afternoon and was met by a handsome young Moroccan named Said. At the school, Said coordinated the volunteers. Anything we needed, he was the person we turned to. But he quickly became far more than that.

Said wasn’t just the one who helped us navigate logistics. He became my best friend in Kelaa, my confidant, my guide through the city, my personal shopper, and the person who showed up without question when I injured my back. In time, he became family. My story this year and here in Kelaa wouldn’t be complete without Said.

January quickly slipped into February, and on the 6th I left Kelaa for Marrakech to meet my dear friend Teri, who was only here for just under a week. I met her at the airport and promptly whisked her off to our hotel, where she could recover by the pool before I introduced her to the beautiful chaos of Jemaa el-Fnaa that evening.

Her first taste of North Africa was a true whirlwind. The next day we wandered the medina, letting ourselves get a little lost, before calling it an early night and the next day catching a morning train to Casablanca. One bucket-list item had to be checked off Teri’s list, Rick’s Café, after which we walked to the Hassan II Mosque and lingered by the sea before catching the train back to Marrakech.

The following day took us by bus to the seaside town of Essaouira, where we soaked in the laid-back, slightly hippie vibe and sipped wine on the beach enjoying the warm the ocean breeze.

Back in Marrakech, we slowed the pace, spending a leisurely day that ended with dinner, drinks, and sunset views from the rooftop at Nobu. Yes, that Nobu, owned by Robert De Niro.

Back in Marrakech, we slowed the pace, spending a leisurely day that ended with dinner, drinks, and sunset views from the rooftop at Nobu. Yes, that Nobu, owned by Robert De Niro.

And then, just like that, she was back in Warren, Ohio, and I was in Kelaa again, settling into a different vibe as Ramadan approached.

The air in Kelaa was warming as everyone anxiously waited for the first sighting of the crescent moon that would mark the start of Ramadan at the beginning of March. I still thought the loose circles penciled onto my calendar marked my farewell to Morocco, but instead, my chapter here extended itself.

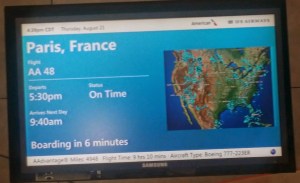

First, a university where I had given a presentation on the U.S. approached me about teaching English for a semester. It was tempting, but I wasn’t ready to tie myself down. Especially with a one-way ticket and two weeks in Paris already planned for April, plus five days in May to give a toast at a special event for the Panther’s Veteran Organization of the 66th Infantry Division and the sinking of the Léopoldville. So, I declined.

Not long after, the English school where I had been volunteering asked if I would teach a full trimester course: two nights a week, two hours each night, for twelve weeks. I explained it wasn’t possible. I already had plans. Paris plans. A flat. A one-way ticket.

Apparently, they sensed a weak moment. Mashi mushkil (Darija for “no problem”), they said. The students could take a two-week break while I was in Paris in April and a short break again in May. I could finish the trimester afterward and still be done in time to head to Bulgaria for summer camp.

And just like that, I found myself searching for a return ticket from Paris to Morocco and committing to teaching a full English course. Proof that Morocco just wouldn’t let me go.

The rest of February slipped by without much fanfare, and before I knew it, we were scanning the night sky for the thin crescent moon that would signal the start of Ramadan. That date that had been circled on my calendar from the beginning for my Moroccan exodus was there for another reason too. I wanted to be there for the entire month, to experience Ramadan fully. What began as cultural curiosity became, in reality, something far more personal.

I won’t write much here about Ramadan. You can read my two-part story here and here, but I will say this: I completed all thirty days of fasting, and I will carry certain memories with me always. The intoxicating scent of orange blossom. A night sky that somehow felt different during that month. The call to prayer, resonating more deeply. Somewhere along the way, I stopped feeling like a visitor observing tradition and began to feel part of Morocco itself.

I felt more grounded, more attuned to the energies around me. I will always remember the iftars spent in the homes of friends, and the final iftar shared with children from the Center for Children in Difficult Situations. More than anything, Ramadan gave me a deeper understanding of a country and a culture I had known so little about and a connection I hadn’t anticipated finding.

I had also begun teaching my English class just before Ramadan started. During those hours together, my students often asked how my fasting was going, and Ramadan created an additional bond between us. It became a shared experience. Something that connected us beyond grammar lessons and vocabulary lists.

The month itself passed in a blur. Before I knew it, I was taking a break from classes to meet two friends, Dawn and Margaret, in Marrakech, before jetting off to Paris for two weeks with another friend, Cathy. I would cross paths with Dawn and Margaret again soon enough, as they passed through Paris for a few days on their way back to the States.

Every so often, my worlds seem to collide, and Paris was no exception. I received a message from Brian, another friend from back home, saying he would be in the city for just one day while I was there. I gave him a whirlwind, one-day tour, my version of Paris, complete with a few favorite stops.

The rest of our time in the city was at an unhurried pace. Aside from a truly fabulous evening at the ballet, we spent our days doing little more than what Paris does best: lingering in cafés and wandering without a plan.

My return to Morocco from Paris included an unexpected and memorable two-day stop in Rome. It was there that I reunited with friends from Florida I hadn’t seen in more than twelve years. It was a reunion made all the more surreal by the timing of my arrival, which coincided with the morning news of the Pope’s passing.

We met at Piazza Navona and, sensing the weight of the moment, decided to walk together toward St. Peter’s Square. The area around the Vatican was solemn yet alive with energy, quiet conversations, and an awareness that history was unfolding around us. After paying our respects and taking it all in, we returned to the piazza for a simple meal and time to reconnect before parting ways.

From there, I boarded a bus to the train station and continued on to a small city about an hour outside of Rome to visit one of the Italian volunteers I had met earlier in Kelaa. I spent the night with her, and the following day she took me on a short excursion to the charming village of Stimigliano. We wandered its cobblestoned streets, stopped for coffee, and soaked in the beauty of the place before it was time for her to see me off. Soon, I was back on a train to Rome and onward to the airport.

And then, it was time to return to Kelaa.

Back in Kelaa, Soukaina, a receptionist at the English school, invited me to spend a weekend in the countryside at her family home. After two taxis and a fifteen-minute walk, we arrived in her village. And when I say village, imagine roughly twenty families living among olive groves, farmland, and open meadows.

What a weekend it turned out to be. I was first treated to a meal of rabbit tajine. Her father had slaughtered the rabbit specifically for my visit. It was both humbling and deeply moving. Over the course of the weekend, I was also treated to two picnics in the olive groves. For one of them, we traveled by donkey cart, carrying everything needed to prepare tajine and tea for about ten people, all to be enjoyed beneath the shade of ancient olive trees.

I learned how bread is baked in a traditional outdoor, wood-fired oven and gained a new appreciation for how demanding life in the countryside can be. Yet what stood out most was the strength of the community. When the neighbors learned of my visit, I was often surrounded by women, laughing, sharing stories, tea, and cookies. I was even introduced to the art of henna and left with my hands beautifully decorated, a visible reminder of a weekend of generosity and tradition.

Back in Kelaa, it was business as usual…classes at the English school, shopping at the souk, late-night dinners with the other volunteers, and, unexpectedly, an invitation from one of my students, Hajar, to her engagement party.

An engagement party, I quickly learned, required a caftan. The girls from the school were thrilled to take me shopping, and it was during this outing that I discovered a local custom I hadn’t known about: caftans are often rented for special occasions. Before long, I was heading home with a stunning turquoise and gold caftan, complete with all the accessories, along with a crash course in the etiquette and expectations surrounding such events.

Still unsure how to properly wear my elaborate outfit, I was grateful when, on the day of the celebration, Khadija arrived at my villa to help me get dressed. Once properly adorned, we set off. I’ll simply say this, an engagement party here is no small affair. It lasts for hours and is rich in food, music, and community.

The celebration began with sweets, followed by roasted chicken, other roasted meats, and, of course, khobz, the traditional round Moroccan bread. There were musicians, singers, and what felt like countless guests filling the small space with energy and joy. After hours of eating, dancing, and soaking it all in, I was ready to head home, but not before Hajar’s mother insisted we finish with a bowl of harira, the beloved Moroccan soup.

Another day, another step deeper into culture and tradition.

Soon it was time for my second trip to Paris in less than a month. This time, my friend Teri joined me, along with a last-minute visit from my former Warsaw flatmate, Zaka. While the company made the trip especially joyful, the heart of the journey carried a deeper purpose.

I had been invited to give a toast at a dinner for the Panther Veteran Organization of the 66th Infantry Division. The toast was in honor of the late Leonard, dear to many, and the person who had introduced me to Lenore, who now heads the organization. Leonard had connected us some years ago, bound by a shared love of Paris, and when Lenore asked me to say a few words about him, I felt both honored and humbled.

We would raise our glasses with Calvados, the apple brandy Leonard had once warned me about when he learned I was moving to Paris. It felt fitting to toast him in the city he loved, with the drink he never forgot to caution me about.

Back in Kelaa, life settled into a familiar rhythm again with new volunteers arriving, past volunteers returning, bougainvilleas bursting into bloom, and the weather steadily warming. At the school, I was wrapping up the trimester I had begun all the way back in February.

During my daily walks to and from the school, I started to notice my lower back “talking” to me. Back problems have been a constant companion most of my life, not to mention the fact that I once broke my back in China, an injury that required a seven-hour surgery. I knew I had probably pushed things a bit too hard in Paris, especially on the hills of Montmartre, but back in Kelaa I convinced myself I could power through it.

I couldn’t.

The pain worsened steadily until, sometime in early June, I reached the breaking point. I’m not sure what the final straw was, but one morning I simply couldn’t get out of bed. I told myself a few days of rest would set things right, after all, I had a commitment at the end of June at Zenira Camp in Bulgaria, and I fully expected to be there.

After nearly ten days with no improvement, I finally gave in and went to the local clinic. They sent me for an MRI, and the results brought unwelcome familiarity: an injury that had plagued me more than twenty-five years ago had reared its ugly head again. I had herniated discs at L4 and L5. And, as a bonus, a brand-new herniation at S1.

I was put on strict bed rest, along with pain medication, muscle relaxants, and anti-inflammatories. It soon became clear that I wouldn’t make the start of camp. As it turned out, I didn’t recover enough to make it at all.

The months of July and August passed quietly as I focused almost entirely on healing. The biggest event during that time was not a celebration, but a necessity…my visa was expiring, and I wasn’t healthy enough to fly anywhere. The only viable solution was a long car journey north to the Spanish enclave of Ceuta, where I could walk across the border into Spain, turn around, and walk straight back into Morocco.

We completed the nearly 800-mile round trip in under twenty-four hours. When we returned, I slept for two full days. The journey reset my visa for another ninety days, carrying me through to the beginning of November.

At the end of August, I moved into a new villa in the Nour district of Kelaa. While it wasn’t as centrally located or easily accessible, I found my rhythm again by relying on a trusted taxi driver I could call whenever I needed to go out. Slowly, I began venturing back into daily life, spending time in cafés, enjoying my nos nos, and stopping by the school when I could, though the six flights of stairs often reminded me that I was still healing.

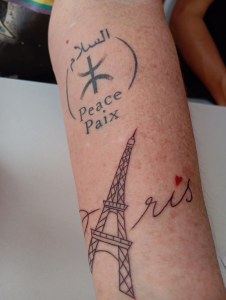

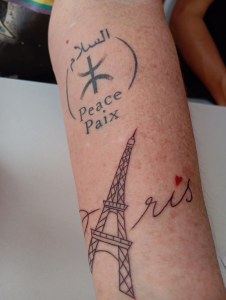

The autumn months blurred together. Time moved strangely, and I couldn’t quite account for where it went. By early October, I finally felt strong enough for a day trip to Marrakech. This time to add to my growing collection of tattoos, each one marking a place where I had lived or spent a meaningful stretch of time. I had gotten my Poland tattoo in December 2024, just before leaving for Morocco, and now I was ready for my “Ode to Morocco.”

Said and I traveled to Marrakech, where I had the words for peace tattooed on my left forearm in Arabic, Amazigh, English, and French. That same month, I began my hijama journey. Similar to Chinese dry cupping, hijama is the Islamic practice of making small incisions before applying the cups. Combined with regular acupuncture sessions every week to ten days, it became a meaningful part of my healing process.

Before I knew it, it was time for yet another visa reset. Still not feeling quite ready to fly, I opted again for overland travel. Not long after, I hosted a near-traditional American Thanksgiving for Moroccan friends and volunteers from the UK and Germany. I even made spaghetti the night before, because some traditions die hard.

Having grown attached to my tattoo artist in Marrakech, I returned in November to add a piece representing my time in Paris. Nothing had quite resonated until then, but eventually the idea came together in a way that felt right. With hijama, acupuncture, massage, and light exercise, I was finally beginning to feel like myself again.

Although my visa situation was stable, I decided to book a December trip to Paris to meet my friend Dawn. Unfortunately, fate had other plans. Dawn fell and broke her shoulder the very evening after I booked my flight and she had to cancel. Still, Paris at Christmastime has a pull of its own, and being no stranger to the city, I went anyway.

As the universe tends to do, things aligned. A friend from my hometown happened to be spending her final night in Paris the day I arrived. We met at Harry’s New York Bar and stayed longer than we should have. She had a long international flight the next morning and may still be blaming me for that. At the same time, one of the volunteers from Kelaa, also coincidentally from Minnesota, was in Paris coinciding for a single day with me. So we met up and I showed him my favorite corners of the city.

Christmas was marked back in Morocco with a shared meal of rfissa and all-American cheeseburgers for five Moroccan friends and volunteers from Connecticut and Mexico. And just like that, I found myself quietly closing out 2025 and beginning to plan my departure from Morocco.

Leaving is an art of its own. It’s rarely easy. But my feet were getting itchy again, and I had a clear sense of where and when I wanted to be next. There were too many signs to ignore.

Morocco, you held me longer than I planned. You wrapped me in your language, your rituals, your food, and your patience. You carried me when my body refused to cooperate and reminded me that healing is not linear.

For that, I thank you.

You gave me exactly what I didn’t know I needed, and just enough time to understand it.

Now the healing is done, the bags are lighter, and the next chapter is already in motion.

I leave not because I must, but because I am ready.

Kenya, I’m on my way.

Back in Marrakech, we slowed the pace, spending a leisurely day that ended with dinner, drinks, and sunset views from the rooftop at Nobu. Yes, that Nobu, owned by Robert De Niro.

Back in Marrakech, we slowed the pace, spending a leisurely day that ended with dinner, drinks, and sunset views from the rooftop at Nobu. Yes, that Nobu, owned by Robert De Niro.

From Asia to Europe to Africa to small-town America, I’ve seen how different our worlds appear and how alike we truly are. We may cook different meals, pray in different ways, or celebrate under different stars, but what we seek, the connection, the comfort, the laughter is the same. Wherever I go, I find the same joy in gathering, sharing, and belonging. Proof that people are far more alike than different, no matter how far from home we roam.

From Asia to Europe to Africa to small-town America, I’ve seen how different our worlds appear and how alike we truly are. We may cook different meals, pray in different ways, or celebrate under different stars, but what we seek, the connection, the comfort, the laughter is the same. Wherever I go, I find the same joy in gathering, sharing, and belonging. Proof that people are far more alike than different, no matter how far from home we roam.

When it came time to leave Xiashan, it didn’t feel like just leaving a place. It felt like leaving a piece of myself behind. I hadn’t realized how much it had become home until that moment. It wasn’t just the people or the place. It was who I had become there. The laughter, the late-night hot pots, the impromptu concerts, and the everyday magic of life there had settled into the corners of my heart. “Only in China,” I thought, as we gathered one last time beneath strings of colored lights and a haze of nostalgia with voices rising in celebration and farewell. I didn’t know it then, but that night marked the beginning of my education in the art of leaving. Learning to say goodbye without truly letting go.

When it came time to leave Xiashan, it didn’t feel like just leaving a place. It felt like leaving a piece of myself behind. I hadn’t realized how much it had become home until that moment. It wasn’t just the people or the place. It was who I had become there. The laughter, the late-night hot pots, the impromptu concerts, and the everyday magic of life there had settled into the corners of my heart. “Only in China,” I thought, as we gathered one last time beneath strings of colored lights and a haze of nostalgia with voices rising in celebration and farewell. I didn’t know it then, but that night marked the beginning of my education in the art of leaving. Learning to say goodbye without truly letting go.

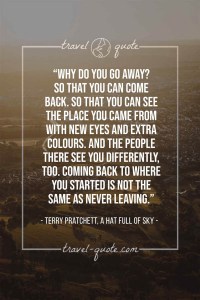

Eleven years ago I packed a single suitcase, certain I was chasing one adventure. Somewhere between missed trains and ever-changing addresses with a revolving door of flatmates, the adventure became my life. Four continents later, the borders blur. Once unfamiliar spices drift through my memories. Friendships, some with fellow travelers who drifted in and out of my days, others with locals whose roots I briefly shared, have become the landmarks of each place. What follows isn’t a checklist of places but a scattering of moments, fragments of the many worlds that now live inside me.

Eleven years ago I packed a single suitcase, certain I was chasing one adventure. Somewhere between missed trains and ever-changing addresses with a revolving door of flatmates, the adventure became my life. Four continents later, the borders blur. Once unfamiliar spices drift through my memories. Friendships, some with fellow travelers who drifted in and out of my days, others with locals whose roots I briefly shared, have become the landmarks of each place. What follows isn’t a checklist of places but a scattering of moments, fragments of the many worlds that now live inside me.