Leaving Kelaa is not an act of escape, but one of completion. By the time February 26 arrives, I know that staying longer would not deepen what has already been given. Kelaa held me when my body needed healing, offering kindness without question and helped me to be present in a life that was not mine, but temporarily borrowed. As I wrote at the close of The Year Morocco Held Me, the next chapter was already in motion. I leave not because I must, but because I am ready. Kenya, I’m on my way. I have been invited to the Mount Kenya Wildlife Conservancy for my next WorkAway project, connected through my long-held support of the William Holden Wildlife Foundation, my admiration for Stefanie Powers’ decades of work there, and newly entrusted with a role in the Mountain Bongo program.

In Part One, I wondered whether the art of leaving was less about goodbyes and more about allowing yourself to be changed. It was about learning how to hold on, even as you go. Those words stayed with me through the months that followed. From May onward, my days in Kelaa were shaped not by plans or timelines, but by routine and familiarity: the steady repetition of ordinary life. Before there was a date on the calendar or a plane ticket in mind, there was simply living. I am the kind of person who one day just knows when my time is over. This time, healing kept me here…until the morning I woke up knowing it was time to move on.

Returning to Kelaa from Paris meant resuming what I had left unfinished: the trimester I had started months earlier, even as I began to think about what might come next.

What I thought would come next never did. I did not make my fifth summer on the Black Sea. An injury kept me home and then the momentum I had been carrying came to a standstill. With movement taken away, I had no choice but to reconsider the story I had been telling myself about what was next.

In those housebound days, my thoughts drifted away from the familiar routes I had imagined and toward something older, unfinished. I thought often of Tanzania, and of the way I had left in 2022 with a sense of incompleteness, a longing to stay that responsibility in Warsaw overruled. I remembered how close I had come, even then, to choosing Kenya over Tanzania.

Somewhere between healing and waiting, Central Asia loosened its grip on me. East Africa returned instead, not as a plan, but as a feeling I recognized.

The “Stans” would have to wait. I thought my sights were set on the Silk Road, back toward China and the place where this journey began twelve years ago. But I have learned to listen to the Universe and to the signs it sends.

A random “like” and a short comment on social media connected me to Nanyuki and the William Holden Wildlife Foundation. The mother of this person had been executive housekeeper when William Holden and Stefanie Powers frequented the Mount Kenya Game Ranch. I had only briefly mentioned my interest in Kenya, and she invited me to meet if our travels overlapped. Another sign: a woman who shares my initials, and also my first name, started following me on social media. She lives in Nairobi and works in the safari industry.

Even in Marrakech, the signs appeared. While getting a Tanzanian tattoo inked, a woman from the U.S. noticed the Kiswahili words I had chosen: nilisafiri, nikajifunza, nikaishi – I traveled, I learned, I lived. She mentioned she was part Moroccan, part Kenyan, and told me her uncle was Maasai and lived near Nanyuki.

Another sign arrived through a Facebook group I had joined at the invitation of a friend from my hometown. Despite sharing 104 mutual friends with the page’s administrator, living in the same town, and even having her husband do work at my brother’s theater, we had somehow never crossed paths…at least not knowingly.

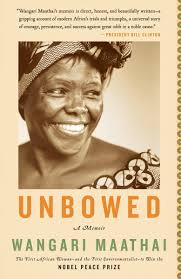

As Kenya continued to surface in my thoughts, I found myself returning to “Unbowed” by Wangari Maathai, a book I had first read years earlier when I was weighing Kenya against Tanzania. Reopening its pages now felt less like nostalgia and more like listening. It was then I learned that this woman had met Wangari herself, another unexpected connection, another confirmation that Kenya was calling. These moments converged until I could no longer ignore them. Kenya was where I needed to go next.

Once the decision was made, the search for a ticket began. A one-way flight from Marrakech to Nairobi was expensive, 700+ euros, but would have taken me through Dubai, where I hoped to see my brother. When that reunion fell through, Morocco still seemed reluctant to let me go.

The ticket I eventually booked routed me through Rome, giving me a two-and-a-half-day layover that felt almost fated. Back in August 2025, I had said “until we meet again” to a young Moroccan girl from the English school where I volunteered. We shared a deep, almost spiritual bond, and when she moved to Italy, we didn’t say goodbye. Somehow, we knew we would meet again. Rome, it seemed, would be our reunion.

With the decision made and the date marked on the calendar, something subtle but profound shifted in my days. Time seemed long and short all at once, as if each moment now carried extra weight. Simple routines, once automatic, became small rituals to savor. I found myself noticing details I’d previously taken for granted and questioning each activity. Would this be the last time I wander through the weekly souk, sip nos nos at this particular café, or take a road trip for Gamila? Every routine act felt heavy with significance, a countdown of the ordinary, compelling me to live each moment fully.

I find myself thinking about all the people I’ve gotten to know, whether deeply or casually. At the BBQ the other night, it was the butcher who always let me take photos and even pose with a giant tomahawk cut of beef; the server who knew I loved the homemade mayonnaise and would bring me the whole squeeze bottle; the guys on the grill who welcomed me behind the counter. I thought of the server at Café Caramel who speaks to me in French and teases me about harissa, and my personal taxi driver, who will pick me up at a moment’s notice, even in his private car, whenever Said or I make a call.

I have thought about the many students at the school with whom I’ve shared stories, laughed, and listened, learning from their devotion to culture and faith. The family I stayed with when I was first injured, and their young daughter. The school owner and his wife, who told me from the start that I would stay in Kelaa, writing “forever” next to my name on the volunteer arrival/departure spreadsheet, with no departure date. The staff at the English School, who included me in so many aspects of their lives.

I wonder if they will think of me a month from now or a year. Did I make a difference? Do they realize how much they shaped my story? Nikki Banas puts it beautifully: “You never know the true impact you have on those around you. You never know how much they needed that smile you gave them. You never know how much your kindness turned someone’s entire life around. You never know how much someone needed that long hug or deep talk.”

And perhaps they don’t even realize the impact they’ve had on me.

And then there are those whose presence makes leaving almost impossible. That person who stepped into your life with such force, such warmth, that it becomes hard to imagine what it was like before they arrived. They shape the chapter itself, leaving you changed, and knowing that when you go, a piece of them goes with you.

I will leave Morocco carrying far more than what fits in a suitcase. It sends me forward with a calmness and patience I did not arrive with, and with a deeper understanding of a culture and faith that taught me how powerful it is to simply share lived experience. It brings me back to one of my favorite lines from Gene Wilder: “My only hope is that even for a moment I helped you see the world a little bit different.” I will carry the warmth in the eyes of a student who wore a niqab. Her eyes that smiled with a kindness I will never forget. I will carry the voice and the broken heart of my fourteen-year-old student who recently messaged me in the early hours of the morning about his first heartbreak, trusting me to hold his pain until he could learn to care again. I will carry the generosity and hospitality of the Moroccan people, something so constant it became the foundation of daily life. I will carry the palm trees framed against the snow-capped Atlas Mountains, and the stillness of the Sahara, where the silence was almost deafening.

More than anything, I leave with peace. The very word tattooed on my arm in Darija, Amazigh, English, and French because peace, to me, is what Morocco means. I am leaving whole, though not unchanged; intact, though deeply shaped. And as I turn toward Kenya, toward acacia trees and wide skies and a new beginning waiting just beyond the horizon, I do so as someone remade by staying, ready now for the next chapter of the adventure.

I leave knowing exactly who I became here. I move on with humility and a sense of privilege, knowing the art of leaving is difficult only when you have been shaped by where you stood. If there is a first star to the right, it is no longer a fantasy but a direction, and I follow it not in search of escape, but toward possibility. Living, as Peter Pan promised, really is an awfully big adventure. Saying goodbye is hard because this place mattered, because the people mattered, and because it means I had something worth holding onto. I step into what comes next not empty-handed, but full. Kenya is not an escape. It is the next chapter. And I am ready.

I held off reading this post because I wasn’t ready to let go of this beautiful place and the people you’ve shared. But today I did and feel inspired once again by your words. Such a beautiful journey you take all of us on, Wendy. Thank you.

LikeLike