Where the Sand whispers and the silence speaks, the Sahara stretches into forever. In January, I set out from Ouarzazate with fellow Warrenite, Eric who had come to visit me in Morocco, on a two-day sojourn that first took us to Zagora and into a small shop where desert scarves were wound around our heads like ancient travelers. From there, the road carried us past the famed sign “52 days to Timbuktu” and the lone tree of life.

Because there were no roads leading to our destination for the night, travel required a 4×4 vehicle, a camel caravan and an organized excursion. We were fortunate to be traveling with Brahim and Mohammed. Brahim comes from a Nomadic family, a local Amazigh (Berber) family who run desert camps. I had spent the last 5 weeks living with his family in Tabounte assisting his children with their English, but also helping with his social media presence for his Sahara Tour business, Caravane, Cimes, et Dunes.

By late afternoon, the asphalt gave way to merely sand tracks that led toward Erg Chigaga. Erg Chigaga is not the desert you stumble into by accident; it must be sought out. Unlike its more visited sister, Erg Chebbi, Chigaga lies deep and hidden, often described as feeling closer to “the true Sahara”. It is sixty kilometers (thirty-seven miles) beyond the last village of M’Hamid, and only fifteen kilometers (nine miles) shy of the Algerian border. There are no paved roads here, only rocky plains, dry riverbeds, and shifting tracks that lead to the horizon. The dunes themselves rise and fall like a golden sea, stretching some forty kilometers (twenty-five miles) long and fifteen wide (nine), with crests that can tower nearly three hundred meters (984 feet).

But, before reaching the dunes at Erg Chigaga, we stopped at a desert camp for lunch. It was tended by a young Nomad, and for that hour it felt as though the whole desert belonged only to us. We were welcomed with the ritual of Moroccan tea. First wafers and peanuts, then the art of pouring. We were told the higher the tea streams from the pot, the greater the respect extended to the guest. I was encouraged to try it myself…the glass filled with froth and sweetness, the wind’s whisper hushed, time seemed to stop, the world stopped turning, and all was focused on that single stream of tea.

Lunch was in true Moroccan fashion. We had a bowl of salad greens with olives, onions, tomatoes, and carrots, followed by a tajine of tender meatballs (kefta) simmered with lentils, all scooped up with warm rounds of Moroccan bread (khobz), After a brief rest, it was time to move on, The sun was already heading westward, and we needed to reach our overnight camp before it slipped behind the dunes.

When we arrived at our desert camp where we would spend the night, Eric and I exited the jeep, slipped off our shoes, and wandered barefoot into that golden sea of dunes. Eric had been told that skin against the earth is the truest way to recharge the body, spirit, and soul. Here we were where the Sahara was at its most untamed. A place where remoteness almost felt sacred.

To stand on the highest ridge of Erg Chigaga is to feel both small and infinite, suspended between the earth and the sky, with nothing but time and silence stretching forever. The vastness seemed to draw close, it had a silence that felt alive until it was broken by the whistle of the wind. Grains of sand tinkled across the surface of the desert and nipped at the exposed skin of our hands and face.

As the shadows were starting to lengthen, we saw Brahim and Mohammed leading our camels to us, their silhouettes slowly taking shape against the amber light.

If you know anything about camels, you know they must kneel before you can mount. At Brahim’s command, our camels sank to the sand. The trick is to wait until they are fully seated before you even attempt to climb aboard. A stirrup helps you swing one leg over quickly before settling into the saddle. Trust me it is not as easy as it sounds.

Once you are seated, there is a handle to grip with both hands to stabilize yourself. Here’s is the critical part, you need to lean back as the camel rises. A camel pushes itself up with its back legs first, causing a sudden jolt forward, sending you lurching forward in a motion that feels like a desert roller coaster.

Well, my camel decided to rise before my second leg was even in the stirrup and I hadn’t leaned back. For a split second, I was certain I’d be catapulted over its head. At the last moment, as the camel straightened its back legs and rocked up on its front, I jolted backward, thankful for that firm grip on the handle and just enough balance to shift into a proper sitting position.

So, off we went, led by Brahim and Mohammed, the swaying gait of our camels carried us slowly into the heart of the desert. Mine, with a bit of personality, kept nipping at the butt of Eric’s. As we rode across a high ridge, we watched the sun starting to spill the last of its light across the sand. If I told you the silence was deafening, then the darkness was blinding, and so we turned back toward camp in the final minutes before the sun lowered itself into the sand for the night.

Our desert camp was simple but surprisingly comfortable. Several unheated tents, each with two double beds, were tucked into a circle around a fire pit. The beds were piled high with thick wool blankets, much needed once the desert night began to bite. The temperatures would dip below freezing. I think Eric even slept in his quilted coat. I had already grown accustomed to cold nights: Brahim’s home, where I had been staying, was also unheated. A shower tent stood nearby, along with western toilets, a dining tent and an open-air canopy with stools and a low table for sharing tea.

By now, six other travelers had joined us. A reminder of humanity in the vastness of the Sahara. Until then, it had felt as if the desert belonged entirely to us.

When the sun finally slipped behind the dunes, we gathered in the dining tent for a traditional meal of soup, bread, olives, and tajine. Afterward, we emerged to find the guides had lit a fire in the pit, and the sky above was beginning to sparkle. Far from any trace of light pollution, the heavens erupted with stars. The Milky Way unveiled itself in all its brilliance, and that January night treated us to an even rarer gift: Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Neptune, and Saturn, all visible at once.

As we circled the fire, the other guides joined Brahim and Mohammed with drums and traditional instruments, filling the night with the rhythm of desert music. When the last flames flickered and only glowing embers remained, the moon rose, nearly full. Its light washed away the stars but bathed the dunes in silver, transforming the desert into a dreamscape. Time stood still once more.

If the air hadn’t been so sharp with cold, I might have slept out there beneath the stars, feeling suspended in another dimension. Instead, I padded barefoot through the cold sand back to my tent, the Eagles’ Peaceful, Easy Feeling looping in my head.

Sometime in the dark, cold hours of night, nature called. As I stepped barefoot into the frigid sand, I was reminded of another night nearly ten years ago, at Mount Everest Base Camp, when I had stood beneath a sky that seemed too vast to belong to this world. That night, jagged peaks framed the heavens; here, it was the soft curves of dunes. Different landscapes, but the same overwhelming pull of infinity above me.

On my way back from the toilets, I paused at the fire pit where a few embers still glowed faintly, like fallen stars. I looked up and just as I had on Everest, I was overcome with emotion. Time dissolved, the silence grew loud, and I felt like the only person on the planet. For that suspended moment, both Everest and the Sahara folded together, as if they belonged to the same dimension, one I was fortunate enough to glimpse twice in my lifetime.

The next morning, I rose just as the sun began spilling over the dunes and the moon still lingering in the sky. For some inexplicable reason, the cold sand and my bare feet had formed a bond, and I trailed barefoot toward the dining tent to see what awaited us for breakfast. Inside, I found Eric, happy about the desert adventure but grumbling about being frozen, wrapped in every layer he had brought. I couldn’t help but laugh.

After a filling breakfast, we packed our things, loaded the 4×4, and found that the other travelers had departed. Once again, the Sahara belonged entirely to us.

We spent the morning driving across dunes, dried riverbeds, and other shifting terrain, stopping occasionally to drink in the scenery. Heavy rains the previous year had given the desert a temporary new face, one unseen for decades. Dried lakes and riverbeds held water again, the sands were dotted with green shoots, and flowers had burst into bloom from dormant seeds.

Navigating this ever-changing landscape was an adventure in itself. Only landmarks could guide our driver as the wind sculpted the dunes into new shapes. Eric quickly dubbed him “Evil Khalid,” much to my amusement.

Eventually, we stumbled upon an oasis, where a lone Nomad welcomed us with tea and offered his wares. I bought a small camel woven from wool. A keepsake I hope will always carry the memory of that extraordinary time in the Sahara.

About an hour after leaving the oasis, the first strip of asphalt appeared. A thin, dark line that signaled we were nearing the edge of the desert. Civilization was creeping back in. We stopped in a small village for lunch, savoring one last moment before the return to paved roads and busier towns. Along the way, the scenery was still breathtaking: rippling dunes softening into rocky plains, and at one point, a Nomad herder guiding his caravan of camels along the road, a timeless image of the Sahara’s rhythm.

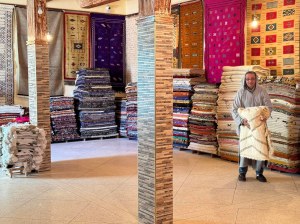

Before reaching Ouarzazate, we visited an Amazigh village and made the inevitable tourist stop at a rug-weaving shop. Obligatory, perhaps, but not without charm. Back in Warren, Ohio, Eric works in the carpet and flooring business, so this stop actually piqued his interest. He listened intently as they spoke of their craft, the symbolism in the patterns, and the tradition of Berber carpets passed through generations.

By late afternoon, we rolled back into Ouarzazate, the desert journey behind us but still clinging in spirit. I still wore my tagelmust, the long, green cloth wrapped around my head to shield me from sun, sand, and wind. It is the traditional mark of Tuareg men, but for me it had become something else: a keepsake of my Sahara sojourn, a reminder of the stillness, the vastness, and the strange way time seemed to fold in upon itself out there.

The desert gave us more than shifting sands and star-filled skies. It gave us a story we will tell again and again. Eric will probably remember the cold nights, the camel with a mischievous streak, and the carpets at the weaving shop that reminded him of home. I will remember barefoot walks across the dunes, music by firelight, and the way the stars shone so bright and close I could almost touch them. Together, we carry the Sahara back with us, not just in keepsakes or photographs, but in the way we felt out there…suspended between earth and sky, small yet infinite, humbled yet alive.

By the time we returned, the Sahara had already become more than a memory. It was a place inside me. Out there, beneath a sky filled with stars, the desert became its own kind of magic, a world outside of maps and clocks. The Sahara was not only vast dunes and shifting light; it stilled me long enough to hear my own heartbeat in its silence. It was a place that stripped away time and left only wonder. And I realized, the little girl named Wendy, you know the one. The one who has never stopped seeking what lies beyond the horizon, had once again stumbled into Neverland. This time it was hidden in the sands of the Sahara, where the night sky itself felt like a map of dreams. Standing barefoot in the cold sand beneath a billion stars, I realized I had once again found my very own Neverland. The Sahara was a world apart, a dreamscape both real and impossible, and like Neverland, it will stay with me forever.

In the end, the Sahara became more than a journey. It became a reminder that wonder is still out there, waiting just beyond the horizon, for those of us who never stopped looking.

“To live would be an awfully big adventure.” – J.M. Barrie, Peter Pan

One thought on “Where the Sand Whispers and the Silence Speaks…A Sahara Sojourn”