About an hour’s bus ride from central Paris, on the far edge of the city sits Chateau de Vincennes. What began in the 12th century as a royal hunting lodge became, over centuries, a fortress fit for Charles V, and later a prison that held notables like the Marquis de Sade and Mirabeau. The chateau sits against the Bois de Vincennes. A little-known forest at the city’s edge.

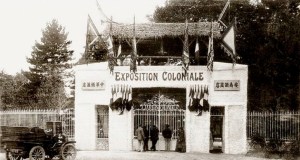

I had visited the chateau before but never wandered into the forest itself. Tucked in one corner lies the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale. First created in 1899 as a research garden with greenhouses for cultivating colonial crops, the garden’s primary function was to test whether tropical and non-native plants and crops like coffee, vanilla, cacao, and banana could be grown in France. It was later transformed, in 1907, into a grand Colonial Exhibition. Afterward, it served briefly as a military hospital during WWI, then as research grounds, before slipping into neglect. When the city of Paris acquired it in 2003, the garden was reopened to the public in 2006, its overgrown ruins and monuments left as quiet witnesses to France’s colonial past.

Among the faded gateways and pavilions lingers a darker chapter, one many visitors may not know. In 1907, the garden also held a human zoo. People from the colonies were brought here and displayed in fabricated “villages” turned into living exhibits for curious crowds.

In April, my friend Cathy joined me in Paris. That day, I didn’t tell her where we were going. I wanted her to feel the full weight of the discovery. We boarded a bus to Nogent-sur-Marne and stepped off in an almost forgotten corner of the city. When we arrived the park was nearly deserted. No children’s laughter, no footsteps crunching on gravel, only stillness in every direction.

I came here knowing what this place once was, and perhaps that is why the silence felt so heavy. It was here, not centuries ago but within living memory, that men, women, and children were displayed like curiosities. The thought is barbaric, almost unimaginable, and yet it had happened right here beneath our feet.

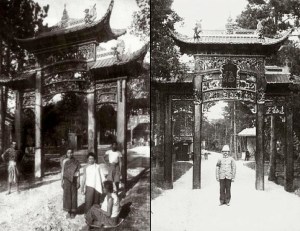

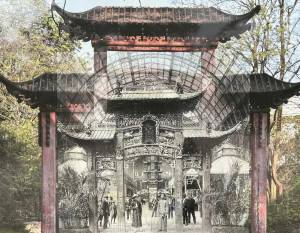

The first thing we encountered was an ornate Chinese gateway, its colors dulled by time but still commanding attention. We wandered deeper into the garden, where vines curled over cracked stone and paths led to abandoned buildings. We passed only two other visitors. The emptiness made it easier to imagine the buzz of past crowds, voices rising in fascination while those on display endured their stares. In that silence the ghosts of the place made their presence known.

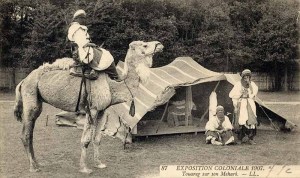

As we wandered, I couldn’t help but think back to what once stood here in 1907. Different “villages” had been constructed, each meant to represent a piece of the French colonial empire in Africa, Asia, and Oceania, including Madagascar, Sudan, Congo, Tunisia, Morocco, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The designers of the exhibition went to great lengths to recreate the life and culture of these places, or at least their version of it, right down to the architecture. The buildings, however, were only the stage. The “exhibit” was the people.

From May to October that year, over one million visitors passed through this garden. They came to watch men, women, and children, entire families, brought from the colonies, lured to Paris with promise of pay and opportunity, only to find themselves transformed into objects of spectacle. The line between human and specimen blurred until it all but disappeared. Behind wooden barriers, they became nameless faces, living displays to satisfy European curiosity.

What happened when the exhibition ended is a question without a clear answer. Few, if any, returned safely to their homelands. Many were likely swept into circus-like troupes that toured internationally, their lives reduced to performances for the rest of the world.

And Paris was not alone in this cruelty. Between 1870 and the 1930’s it’s estimated that more than 1.5 billion people visited similar exhibitions worldwide in cities such as Hamburg, London, Milan, Amsterdam, as well as New York and Chicago. Even as late as 1958, almost within my lifetime, the Universal Exposition in Brussels included a display of Congolese people behind fences. A so-called “village” of living humans. It was the last of its kind, finally closing when the exposition ended that October.

The Jardin d’Agronomie is hauntingly beautiful. We wandered through what remained of the villages. The pavilions sagging under the weight of time, their architecture now more a suggestion than structure. There is a manmade stream that winds toward a still and murky pond. The air is heavy with the silence of a place that once held noise, laughter, spectacle, and most likely sorrow.

Here and there, statues and war memorials from the 1931 Colonial Exhibition stood among the trees like guardians of memory. The garden itself was haunting, not just because of what remained, but what could no longer be seen. The people whose lives once filled this space. The war memorials told one story. The pavilions whispered another. Together they made a strange harmony of beauty and unease.

As we circled back to the ornate Chinese gateway, I found myself thinking about what it means to travel. Travel, I realized is not only about what delights the eye, but about where the heart hesitates and where history unsettles us. In the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale, beauty and cruelty lie side by side, and the ruins remind us that memory is fragile. It is our task not to look away.

Paris dazzles with its light, but here in this forgotten corner, I found its shadows. To walk these paths is to become a witness, to listen to what the silence is still trying to say. As James Baldwin once wrote, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Some places you visit for beauty, others for truth. This garden holds both. And Paris may call itself the City of Light, but here, the shadows insist on being seen.